Leptomeningeal Disease Diagnosis - Words of Encouragement

Recently a dear friend was diagnosed with Leptomeningeal Disease.

This is a terrifying diagnosis in an already difficult disease. As the wonderful Emily Garnett has described so poignantly in her blog about how she felt when she had gotten the news of this diagnosis.

“So this was pretty terrible news. Actually it was the absolute worst news. Left untreated lepto mets can spread very rapidly, often causing someone to die in a matter of weeks, maybe months. Even with conventional treatment options, life expectancy is considered in the span of months.

I felt and continue to feel the narrowing of the lens through which I view my life. Making plans for weeks, even months ahead of the now, is a trigger for me. More often than not, when a well meaning acquaintance makes an offhanded remark about an indeterminate time in the future, I'm reduced to tears. I know the likelihood that I will see that time is very small.”

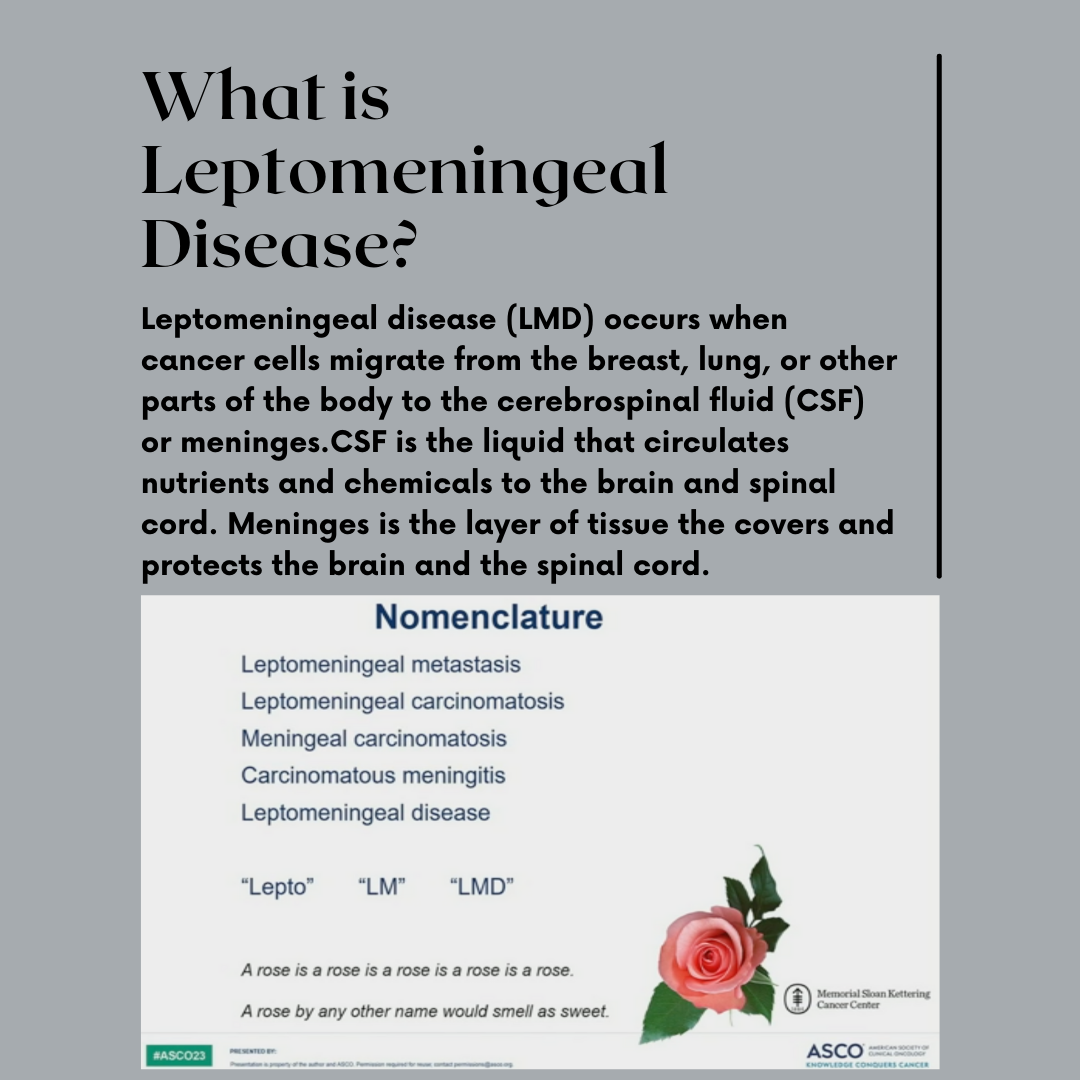

Leptomeningeal disease (Lepto, LM or LMD) occurs when cancer cells had crossed into cerebral spinal fluid or CSF and are circulating within that fluid. It is a relatively rare complication of cancer and occurs in approximately 5–8% of patients with solid tumors.

So what do you say to a friend who just received this diagnosis? How can you help? What words do not sound like platitudes? What is that fine line between encouragement and false hope?

I feel that the only help I can offer, is by sharing my knowledge and understanding of metastatic breast cancer, and my ability to disseminate important news and information. I know my friend has a sound plan of action. She is in good hands and treated in one of the best cancer centers in the world.

Still…

I would probably start by saying this:

As survival rates from other cancers improve, more people are having to cope with this complication. Fortunately, recent advances in cancer therapies promise more options for effective treatment. I hope you understand that much of what you may hear and read is already outdated.

Here are some updates that are up-to-date, and you might find them helpful.

Introduction

On June 5th, 2023, a special education session, entitled “ Leptomeningeal Disease: Toward Patient-Centered Care and Research for a Pressing Clinical Problem” was held in Chicago’s McCormick Place, the site of the ASCO annual conference. Unfortunately, I was unable to attend this session in person, but luckily for me it was recorded and archived. I went over audio and slides many times and tried to understand and take in every word. It was that important.

I would like to share my notes with you, our community.

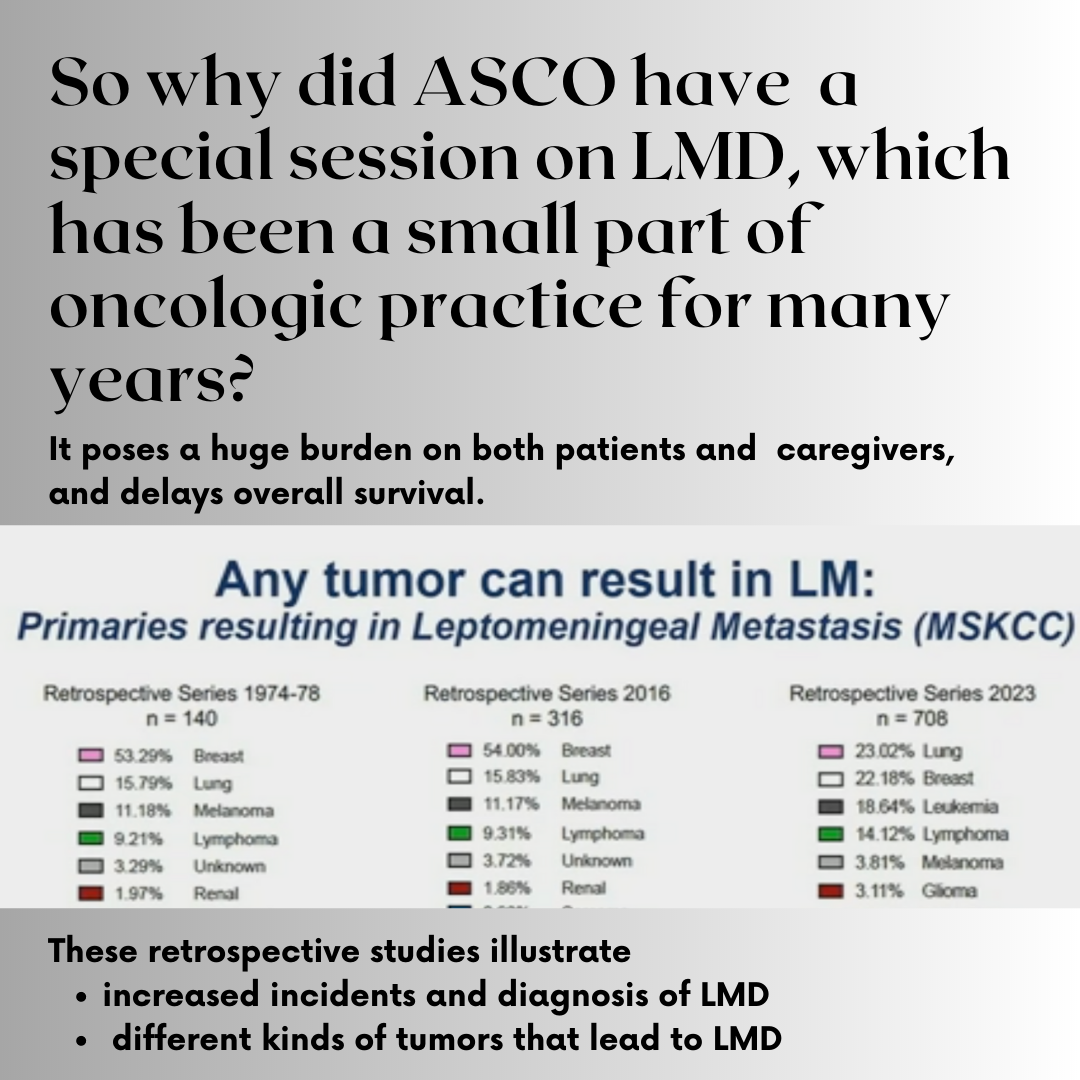

At the start of the session, its chair Dr. Adrienne Boire of MSKCC, posed a question:

“So why are we having a session in this enormous theater about Leptomeningeal Disease?”

“This is promising,” I thought. LMD is a rare complication, that was often overlooked by the mainstream science. Why indeed? Is the number of people who get this diagnosis, growing? Does it have anything to do with better treatments and longer survivals for patients with CNS metastases? What about treatments themselves? Are there more of them and, and thus this timely ASCO discussion?

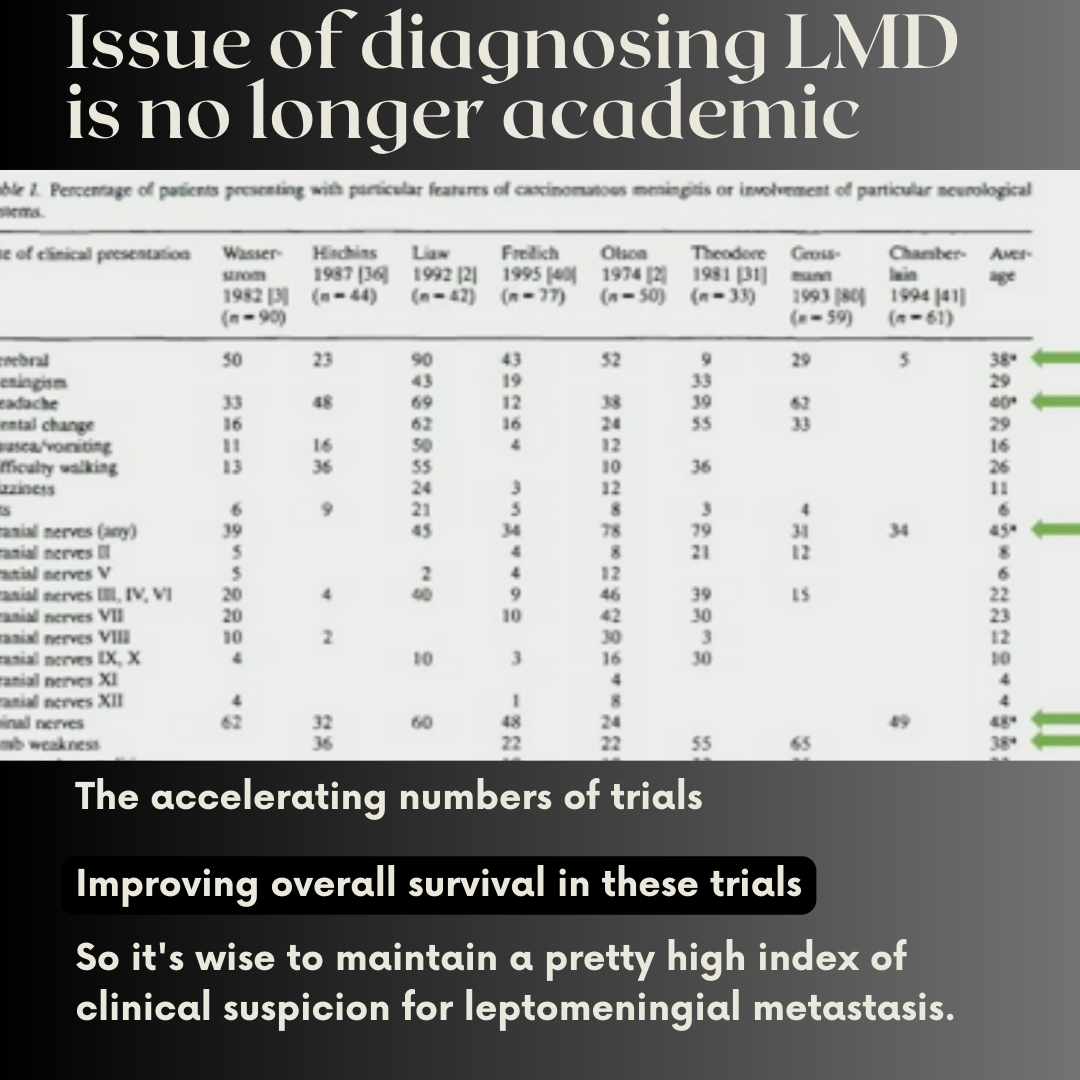

It turns out that the answer is “Yes” to all my questions. New opportunities for therapies and for predicting therapeutic response have recently become available. The number of clinical trials is growing and accelerating. Overall survival is also improving for patients.

And unfortunately, the answer is also “yes” to a question about increased incidents in the diagnosis of LMD.

One of the widely accepted explanations is that Leptomeningeal Disease is increasing in numbers as people are living longer with advanced cancer.

LMD is almost never the first site in metastatic setting, that happens only in 5–10% of patients. It is usually a result of advanced disease progression with the median time from the diagnosis of metastatic disease to LMD ranging from 1.2–2 years in solid tumors. Roughly 50 to 80 percent of people (depending on the study) who have LMD also have brain metastases (within the brain rather than within the spinal fluid).

Clearly, the organizers of ASCO 2023 feel that LMD was a pressing clinical problem and diagnostic challenge that required a special education session at the ASCO annual meeting.

This session provided updates on the diagnosis and management of leptomeningeal metastases including systemic and intrathecal therapies, radiotherapy, and palliative care, with a focus on bringing access to new technologies to all patients.

To sum up, LMD is still an area of a huge unmet need, but improving

More trials

Better Overall Survival

Accelerating number of trials

Chapter 1: Advances in Diagnostics and Response Assessment for Leptomeningeal Disease

Dr. Adrienne Boire, Neurologist & Neuro-Oncologist, MSKCC

Leptomeningeal disease is also known as carcinomatous meningitis or neoplastic meningitis. Most often with this complication, people have multiple neurological symptoms including visual changes, speech problems, weakness or numbness of one side of the body, loss of balance, confusion, or seizures. Diagnosis is usually made with a combination of an MRI and spinal tap.

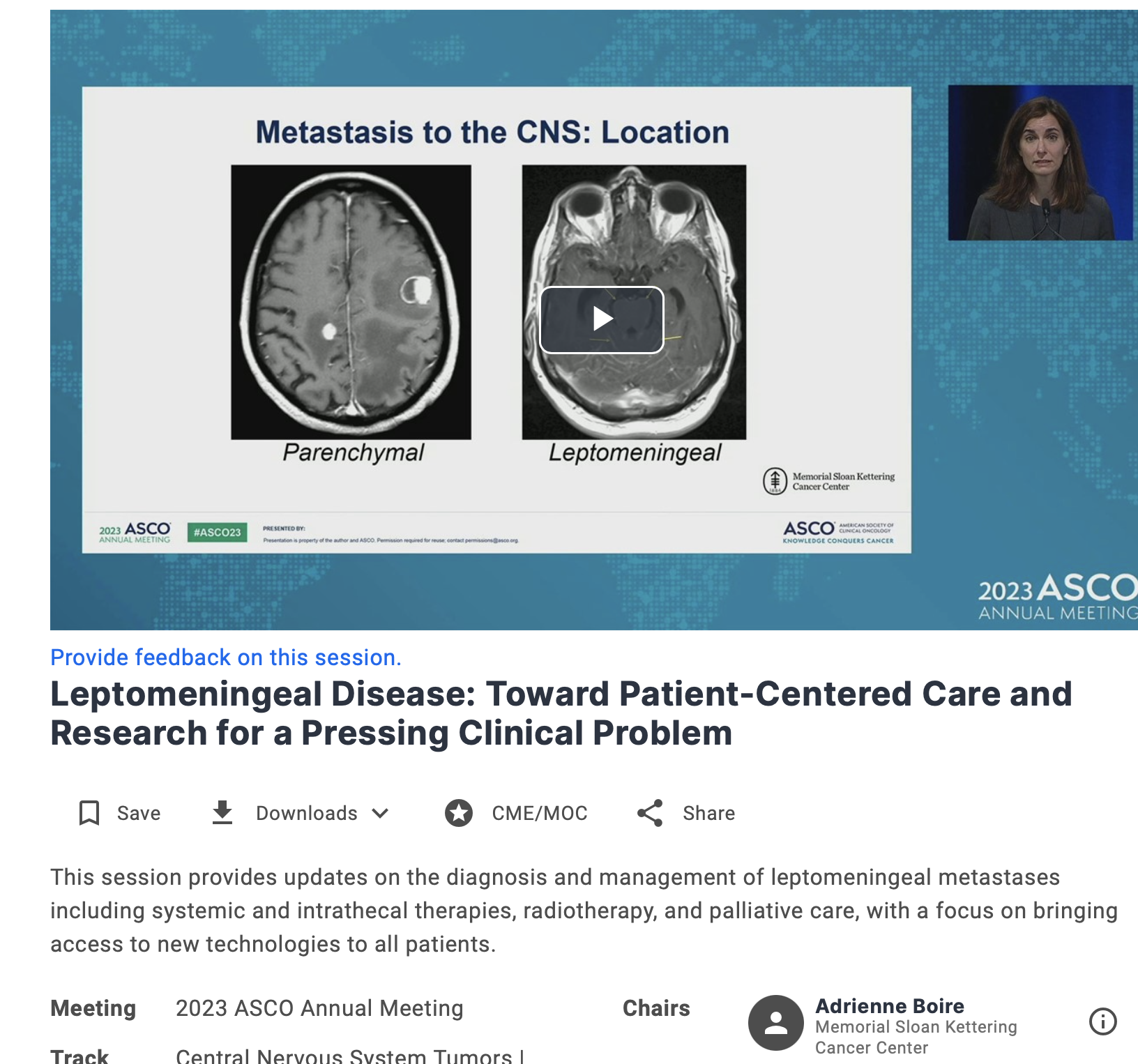

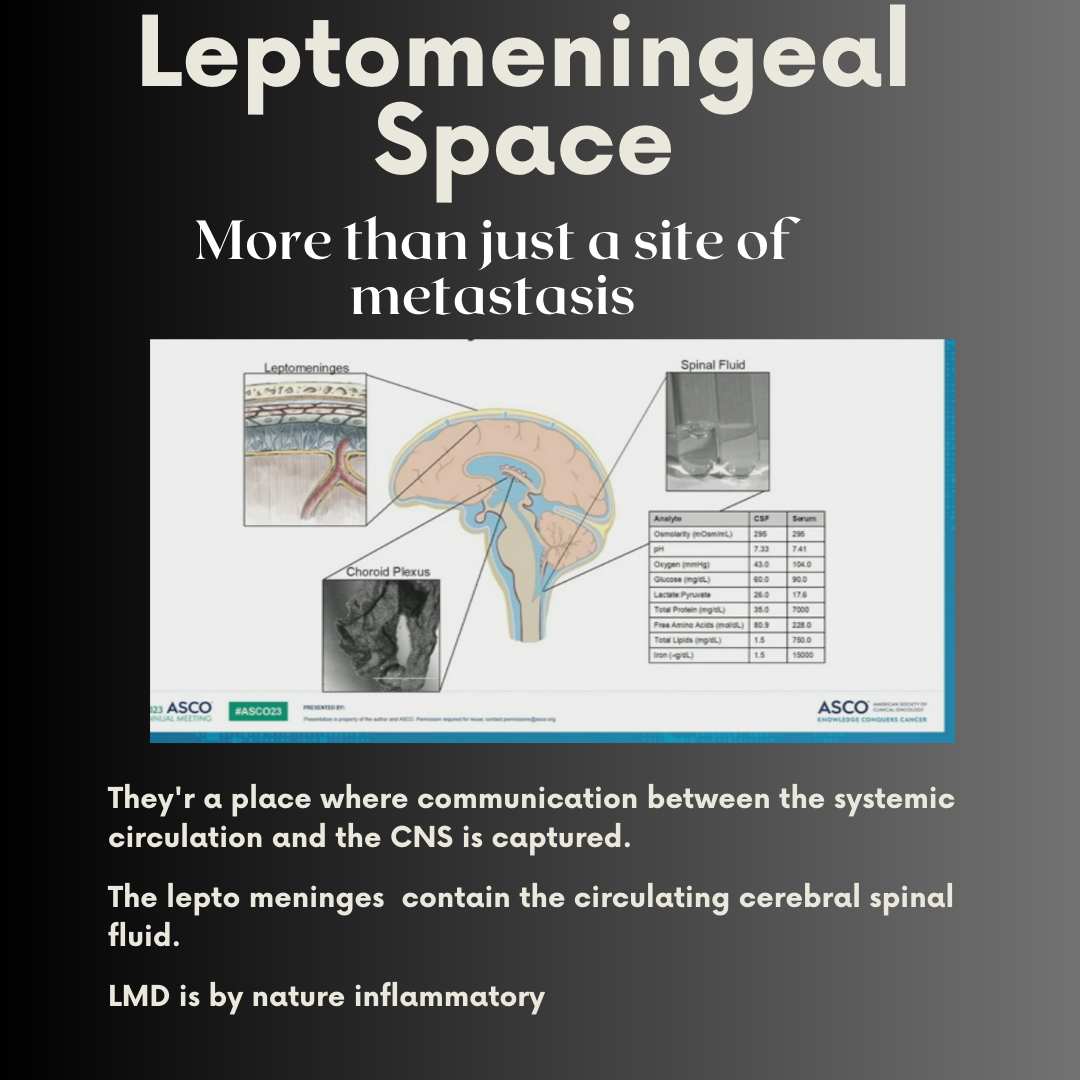

Unlike the spread of cancer to the brain itself (brain metastases), leptomeningeal metastases involve the spread of cancer cells to the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that bathes the brain and spinal cord. It arises due to the seeding of cancer cells into the leptomeninges, the two innermost membranes that cover and protect the brain. Cancer cells may float freely between these membranes (the subarachnoid space) in the cerebrospinal fluid (and hence travel throughout the brain and spinal cord). Because cerebrospinal fluid is rich in nutrients and oxygen, cancer cells don't need to form large tumors to be viable, as they do in other regions of the body.

Diagnosing leptomeningeal disease can be challenging, not only because of the overlap of symptoms with those of brain metastases, but because of the testing process. A high index of suspicion is necessary to ensure that the appropriate tests are run for a timely diagnosis.

-

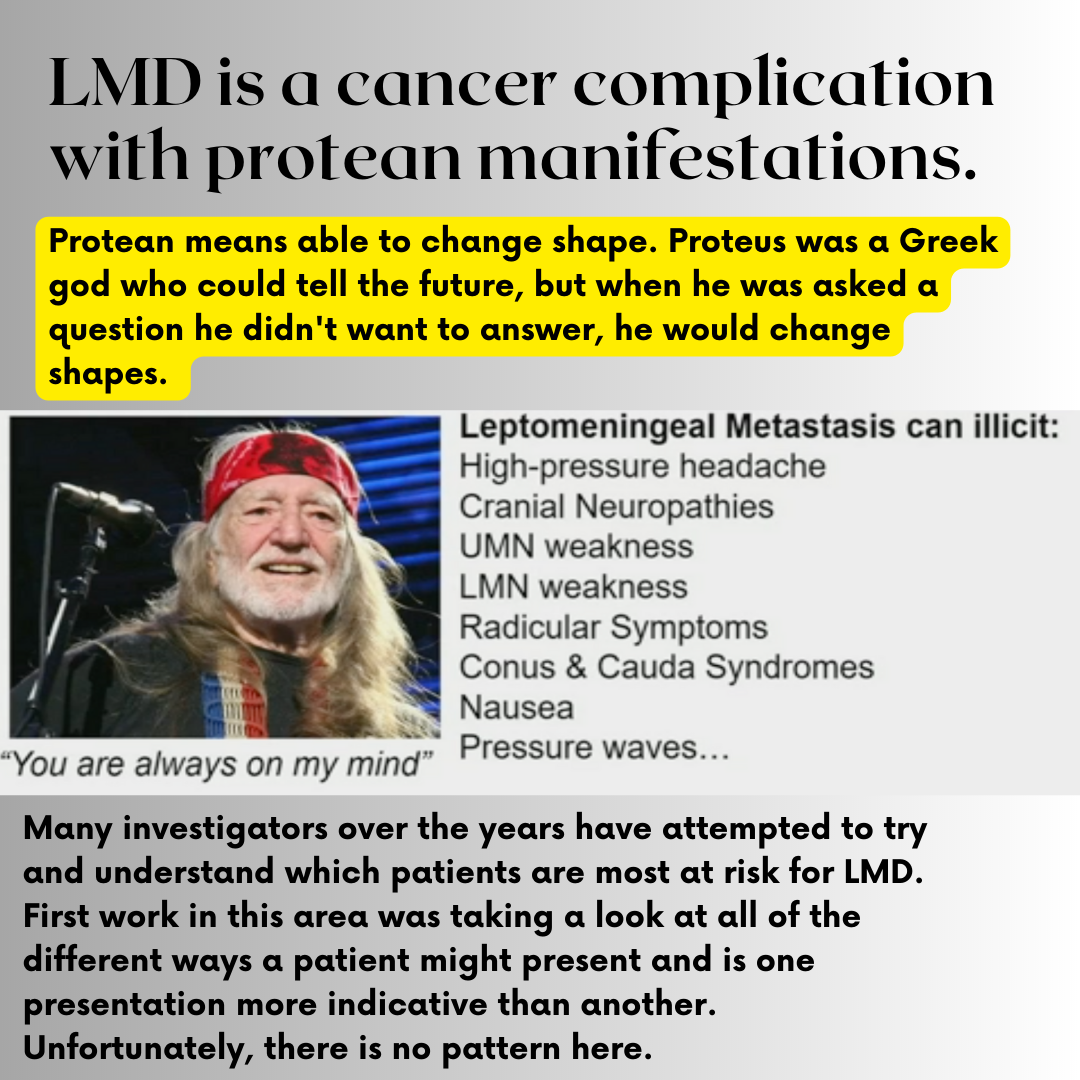

Many investigators over the years have attempted to try and understand which patients are most at risk for lepto, and the first work in this area was taking a look at all of the different ways a patient might present and is this is one presentation more indicative than another of LMD These investigations confirmed that there was no predictive pattern

-

The standard line in most textbooks is that leptomeningeal metastasis is a cancer complication with protean manifestations. Protean means able to change shape. Proteus was a Greek god who could tell the future, but when he was asked a question he didn't want to answer, he would change shapes.

leptomeningeal metastasis can elicit a number of neurologic symptoms, including high pressure headaches, cranial neuropathies, upper motor neuron and lower motor neuron pattern weakness, and nausea, as well as pressure waves text goes here

-

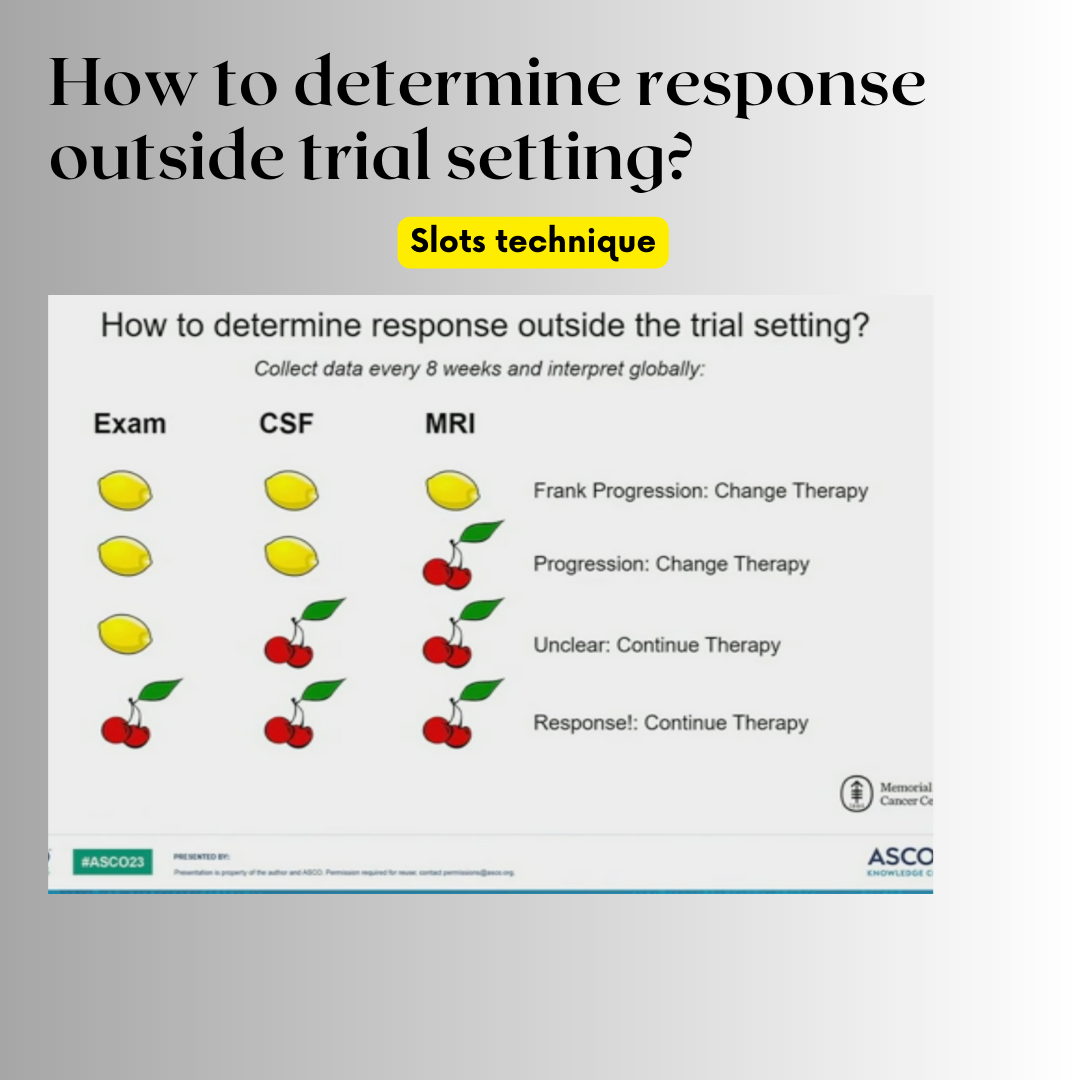

It takes two parts in order to successfully diagnose LMD: MRI and CSF sampling.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and spine, with and without contrast, is the gold standard in diagnosing leptomeningeal disease. Sometimes the disease occurs only in the spine and not the brain, and therefore a scan of the full spine and brain is recommended. On an MRI, radiologists can see inflamed meninges and any co-existing brain metastases.

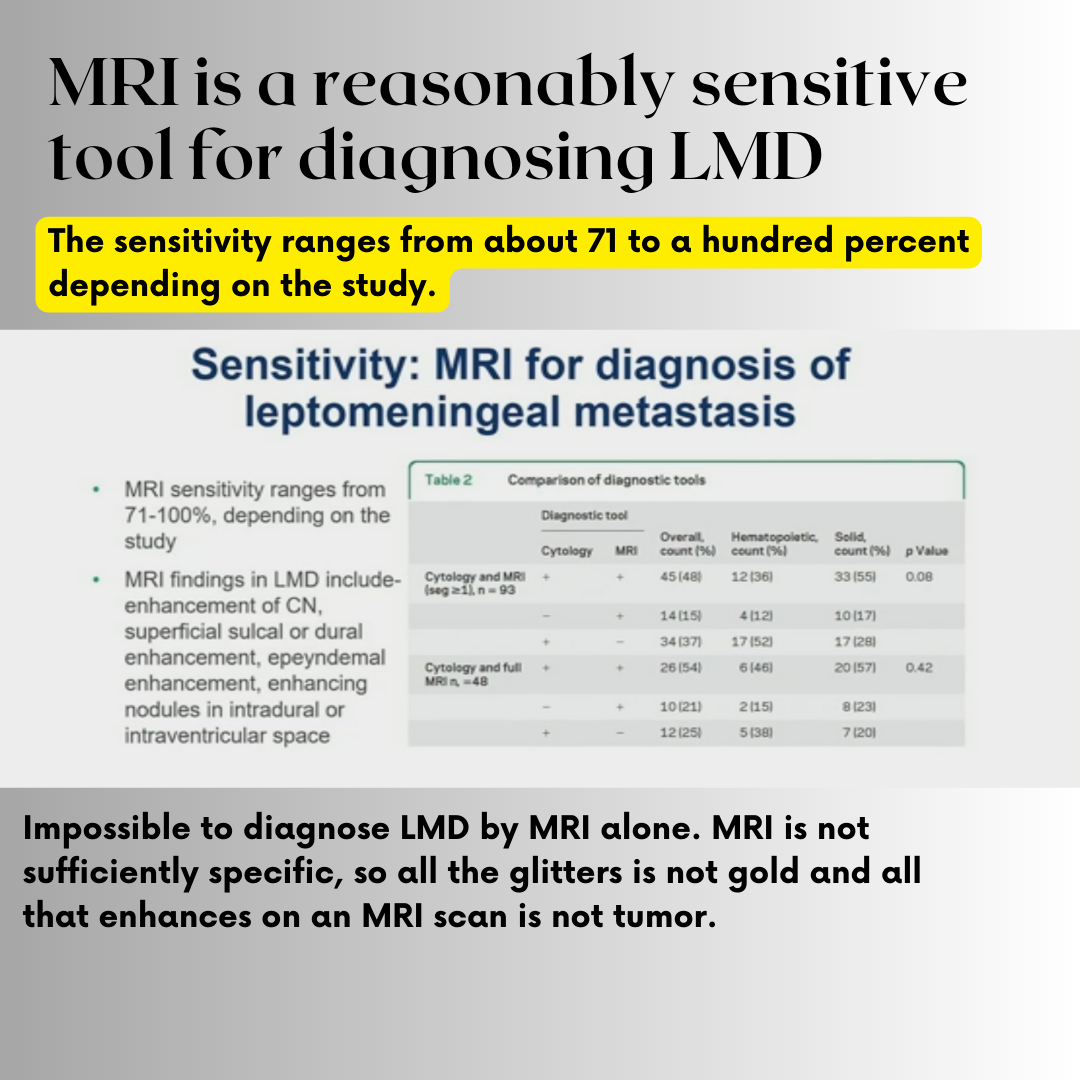

MRI is a reasonably sensitive tool for diagnosing lepto metastasis, and the sensitivity ranges from about 71 to 100% depending on the study

These findings may give false impression that lepto can be diagnosed by MRI alone, however, MRI is not sufficiently specific, just like all the glitter is not gold and all that enhances on an MRI scan is not tumor.

MRI alone cannot secure the diagnosis of LMD in the era of immuno-oncology, we need CSF

-

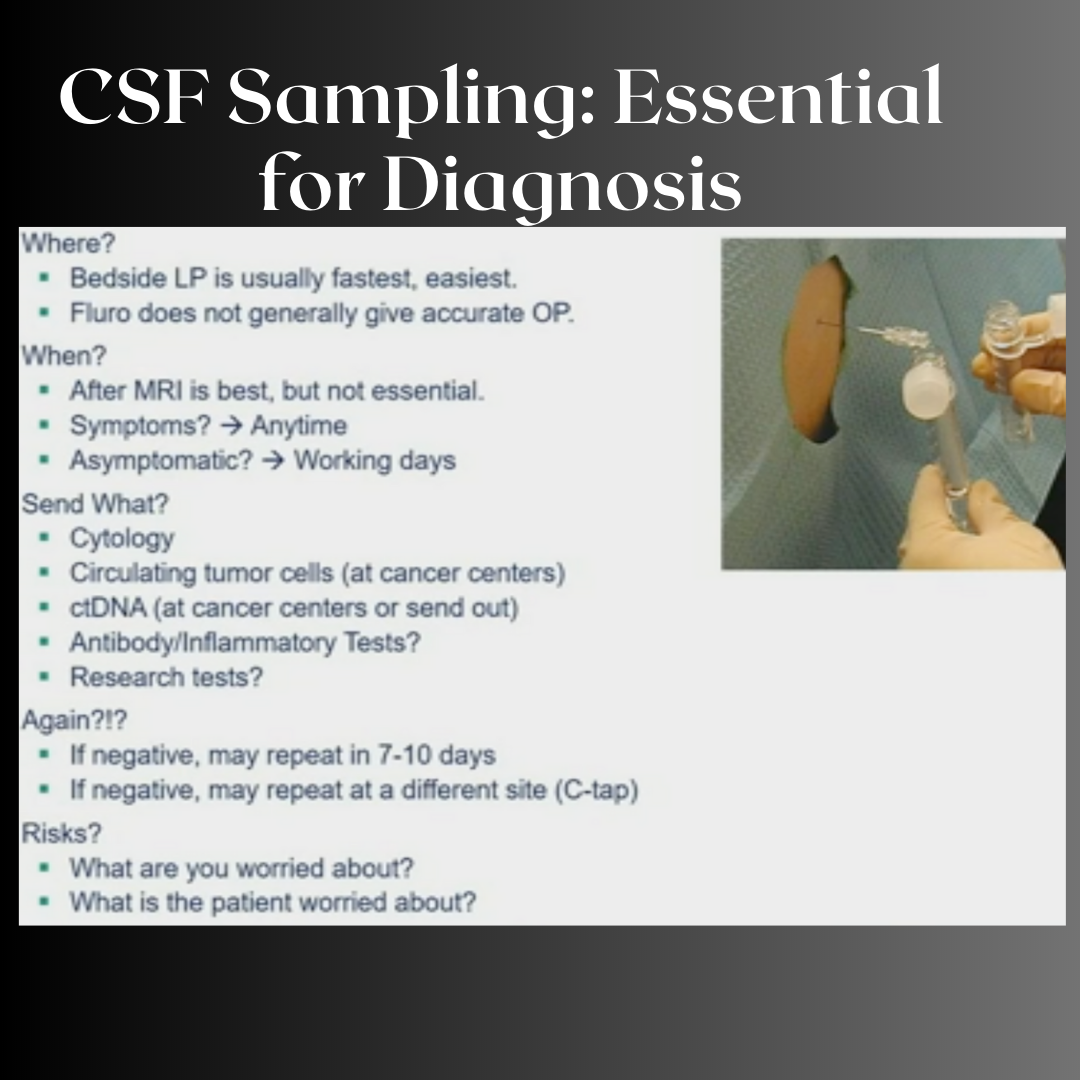

Where and when to do lumbar puncture?

Bedside

Lumbar puncture by the bedside is the fastest and the easiest way. If the patient has symptoms, it's wise to perform the lumbar puncture at any time.

What about risk and pain, associated with lumbar punctures?

178 patients were asked about their perception of pain before and after lumbar punctures. The patients predicted that the procedure would be painful as on an average of about 3 out of 10, afterwards they reported an average of 0 out of 10. And more than 79% of the patients agreed to do a subsequent lumbar puncture if needed.

-

If leptomeningeal metastases are suspected, a lumbar puncture (spinal tap) is often recommended as the next step. Before this test, doctors carefully review the MRI to ensure that a spinal tap will be safe. Positive findings on a spinal tap include:

Cancer cells, which are not always detected, and a tap may need to be repeated,

An increased number of white blood cells (WBCs),

The first component of the basic CSF testing is the cell count. A normal cell count is less than 4 per millimeter cubed, suspicious between 5 and 10, and abnormal > 10. And this is because normally, CSF is nearly completely acellular.

An influx of immune cells is always a sign of pathology and should not be ignored.

An increased protein content,

Standard CSF chemistries include protein. Normal protein of about 15 to 45 (usually around 40). Inflammatory processes generally increase the CSF protein and the site of collection is important.

A decreased glucose level.

The chemistries including glucose. Normal glucose levels are between 45 and 80 or two-thirds of the circulating blood glucose.

LMD within the spinal fluid is marked by a low glucose level, and this is because inflammatory processes within the spinal fluid will lower the CSF glucose.

-

The old school way of looking at spinal fluid is cytology. Any hospital can do this and it has low sensitivity, hence the need to sometimes repeat a study, but has reasonable specificity and can reliably identify cancer versus non-cancer.

Circulating Tumor Cell technology has been adapted to the spinal fluid and has really changed the field. Most cancer centers are able to do it. It's based on surface markers, including EpCAM

Circulating Tumor cell technology has been adapted to the spinal fluid and has really changed the field.

It is able to quantify the number of cancer cells and really establish a quantitative response to therapy.

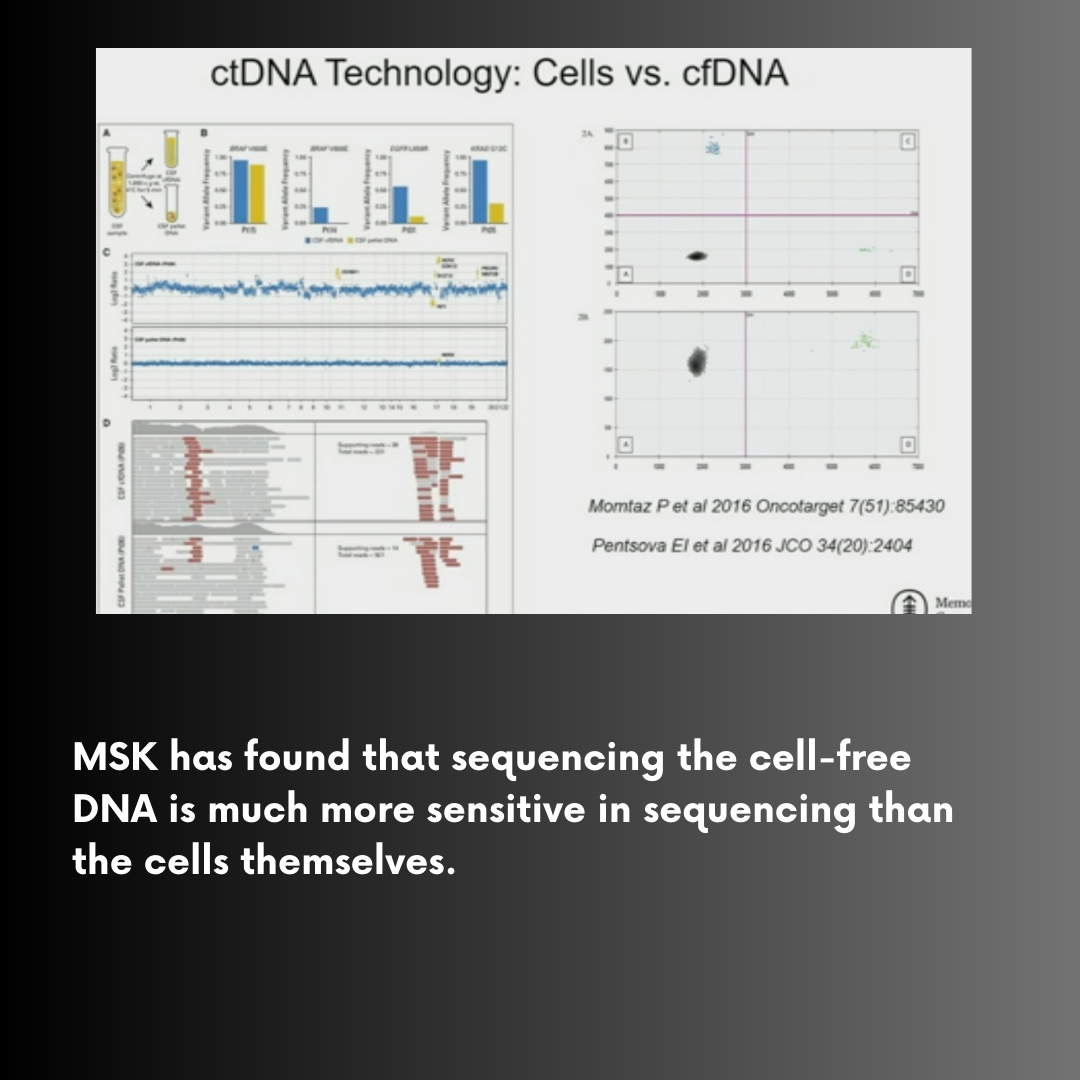

We've really taken something that was a binary variable, yes or no, presence or absence of cancer into a non-binary one. Circulating tumor cells are really just the tip of the iceberg in terms of our modern CSF studies or liquid biopsies. And these identify not just the cells within this space, but also allows to be able to perform cell-free DNA sequencing

The reason that this is important is because metastasis is fundamentally an evolutionary problem. As a primary tumor invades and disseminates, it will continue to evolve over time. And metastases within the central nervous system undergo not just therapeutic selective pressure, but also the intense environmental selective pressure of the central nervous system.

Chapter 2: State of the Art Use of Systemic and Intrathecal Therapies for Patients With Leptomeningeal Disease

Dr. Emille La Rhun, Senior Specialist in the Department of Neurosurgery.

Best Treatment for LMD - Personalized Treatment

The treatment of leptomeningeal metastases depends on many factors, including severity of symptoms, type of primary cancer, the person's general health, presence of other metastases, and more.

Leptomeningeal metastases are challenging to treat for several reasons.

They often occur in advanced stages of cancer and after a person has been ill for a significant period. Because of that, those diagnosed with the disease, may be less able to tolerate treatments such as chemotherapy.

As with brain metastases, the blood-brain barrier poses problems in treatment. This tight network of capillaries is designed to prevent toxins from getting into the brain, but for the same reason it limits chemotherapy drug access in the brain and spinal cord. Some targeted therapies and immunotherapy drugs, however, can penetrate this barrier.

The symptoms related to leptomeningeal disease may progress rapidly, and many cancer treatments work relatively slowly compared to disease progression.

LMD is classified as Type I (definitive diagnosis with positive CSF cytology or biopsy) or Type II (suspected, from clinical findings and MRI only)

Intrathecal pharmacotherapy

Intravenously administered chemotherapy drugs don't usually cross the blood-brain barrier,

Example below shows how ineffective an IV infusion is in delivering the drug to CSF. The penetration is measured by the CSF/plasma ratio, the difference between what is given in IV and how much will penetrate into the CSF.

As an example, Trastuzumab,, if delivered intravenously will result in a maximum of 2% penetration.

For this reason, the drugs are frequently injected directly into the cerebrospinal fluid. This is referred to as intraventricular CSF, or intrathecal chemotherapy.

Intrathecal chemotherapy was once administered via a spinal tap needle. Today, surgeons usually place an Ommaya reservoir (an intraventricular catheter system) under the scalp, with the catheter traveling into the cerebrospinal fluid. This reservoir is left in place for the duration of chemotherapy treatment.

Evidence for Benefit of Intrathecal Therapy

This small randomized study illustrates that intrathecal delivery of systemic treatment improves the PFS (the primary endpoint).

In addition, a retrospective analysis of the cohort of 254 patients, collected from different sites, showed that patients with Type I LMD (definitive diagnosis, presence of tumor cells in the CSF) benefited from intrathecal treatment.

This, however, was not the case for patients without tumor cells in the CSF.

Clinical Trials for Intrathecal Trastuzumab

With HER2-positive breast cancer, the HER2-targeted therapy trastuzumab (Herceptin) can also be administered intrathecally.

Systemic Treatments

It's important to control cancer in other regions of the body as well, so specialists often use additional treatments along with intrathecal chemotherapy and/or radiation.

So here are some data in breast cancer. Unfortunately, there are no Phase III trials.

To sum up,

Chapter 3: Use of Radiotherapy for Leptomeningeal Disease: Applying Trial Data to the Real World

Michelle Alonso-Basanta, MD, PhD, Chief of the Central Nervous System, Service in Radiation Oncology, UPenn

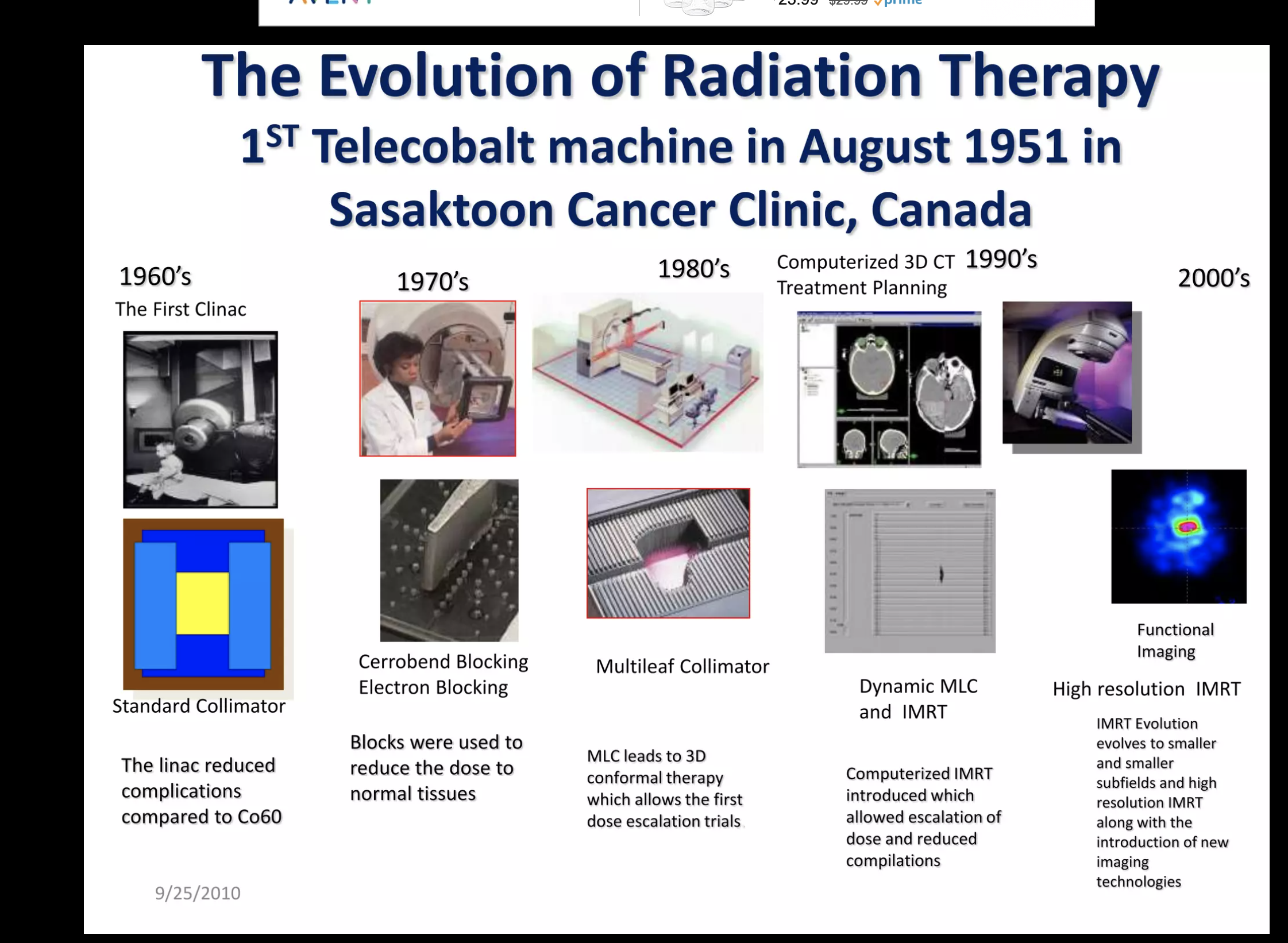

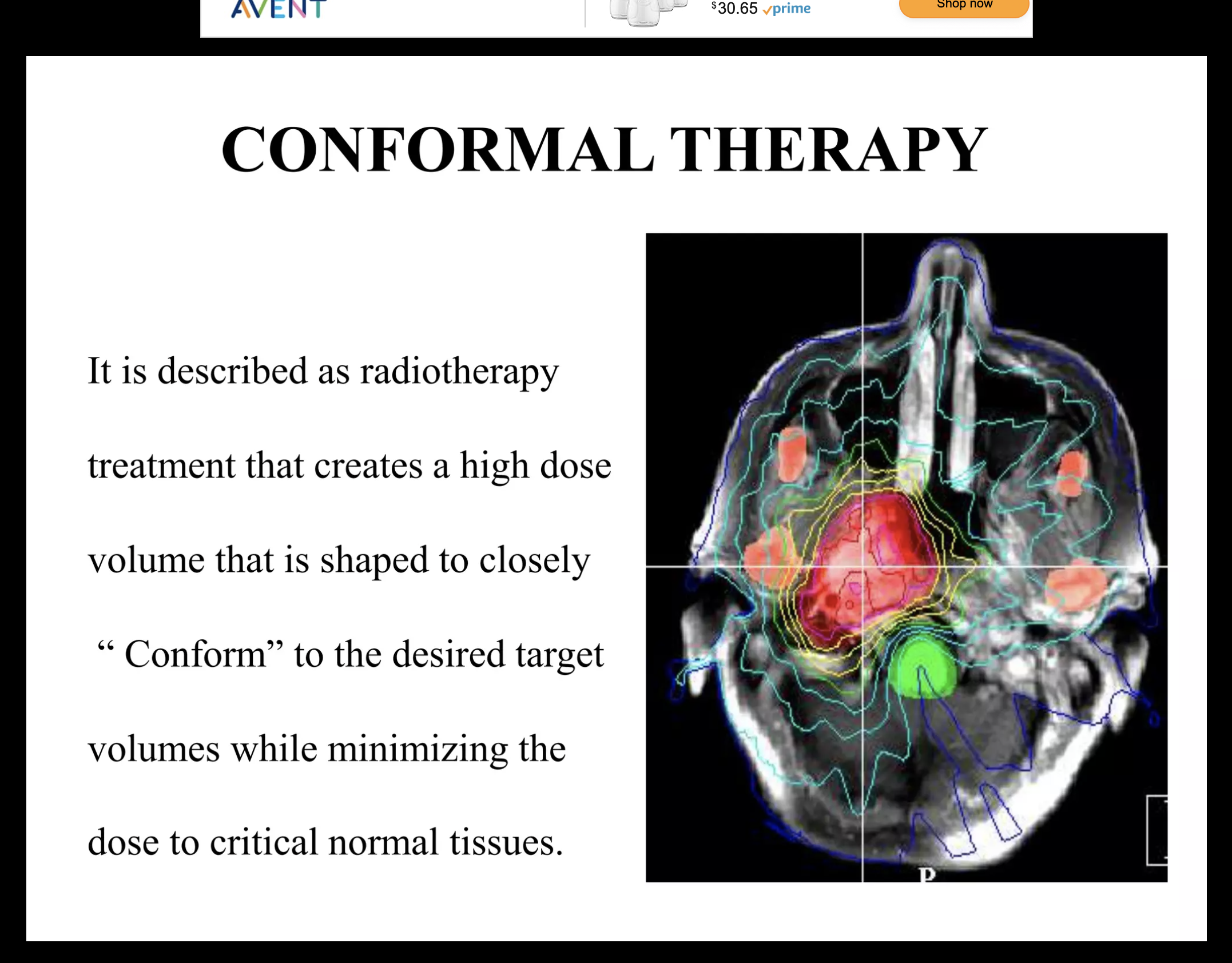

Photon involved-field radiotherapy (IFRT) of whole brain and spine is the standard-of-care radiotherapy for patients with leptomeningeal metastasis (LM) from solid tumors.

To an experienced radiation oncologist, the whole brain and spine fields are fairly simplistic for calculation of a 3-D simulation, and they can be calculated quickly. For this reason they've been considered palliative workhorse. That’s essential when a patient needs to get on treatment very quickly.

A serious limitation to this type of radiation - it assumes no prior radiation. In this day and age, doctors see very few patients with no prior radiation.

It does a very good job at relieving symptoms, but it does not have an impact on survival because, in essence, only a portion of the disease is being treated.

Craniospinal Irradiation or CSI is a much more complicated and calculated process and treatment. The transition for most radiation oncologists from children to adults was not easy. And traditionally, the prone (face down) position was used because of the techniques available at that time.

Historically, when the craniospinal irradiation was offered in the metastatic setting, it was usually over 4 weeks with at least 2 weeks of recovery

Patients who needed to control their systemic disease and had to resume their systemic treatments were not good candidates for this therapy.

So patient selection was always key. It was always part of the discussion and the overall performance status was essential, because doing this treatment is not inconsequential, both in the length of time on the table.

The biggest disadvantage of the prone position (face down) is that it is extremely uncomfortable to a patient.

For a radiation team, it had some advantages, but the disadvantages clearly outweighed the advantages, so there was a move in the field to treat supine.

Figuring out how to perform this technique in supine (face up) position was a great boost to craniospinal irradiation.

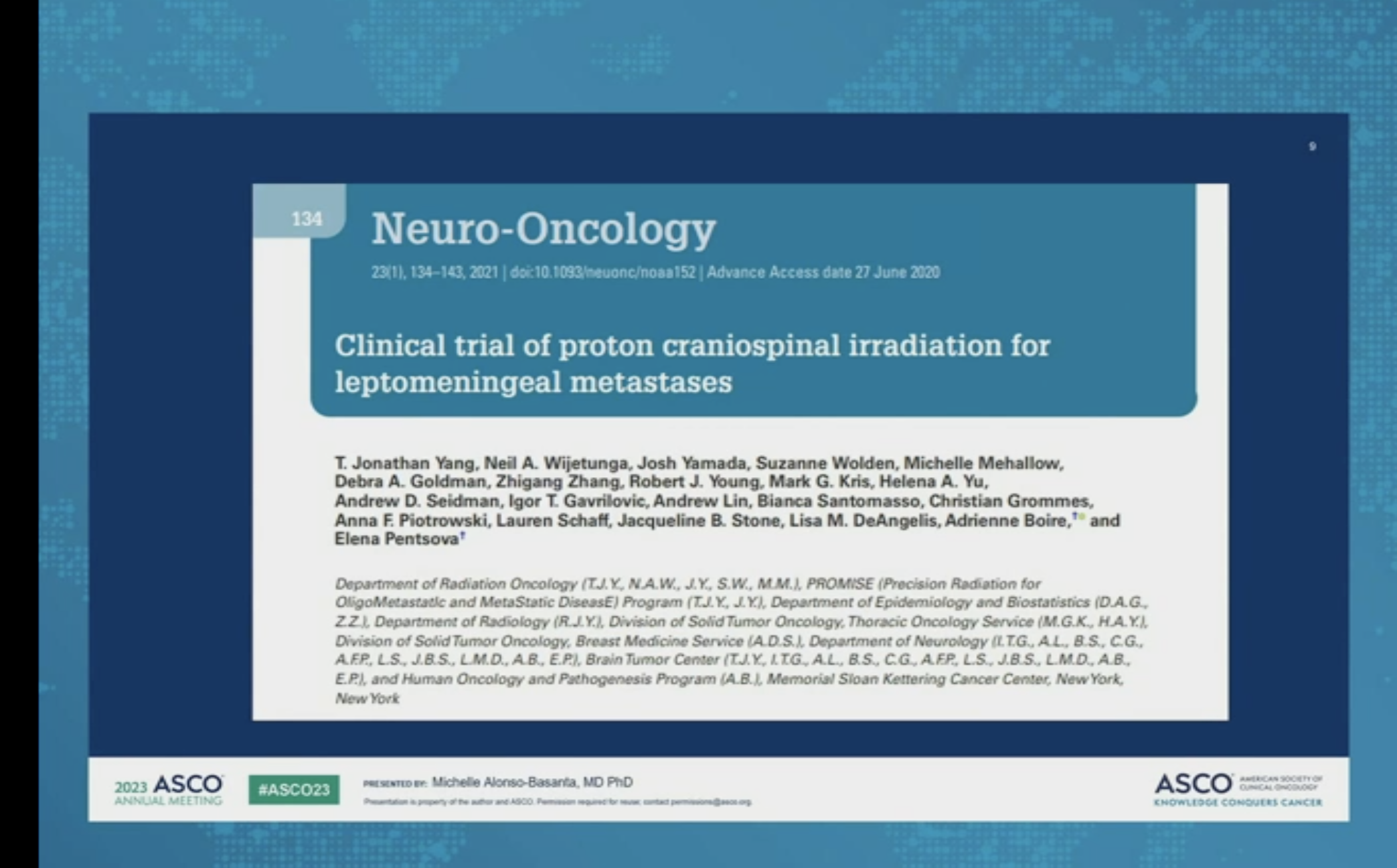

Still, this is not a technique that can be done in a day. So why are we even talking about it so much? About two years ago, the Phase IA/B trial came out from MSKCC looking at pCSI or proton craniospinal irradiation for both lung and non-small cell lung cancer with expected good overall survival and progression-free survival.

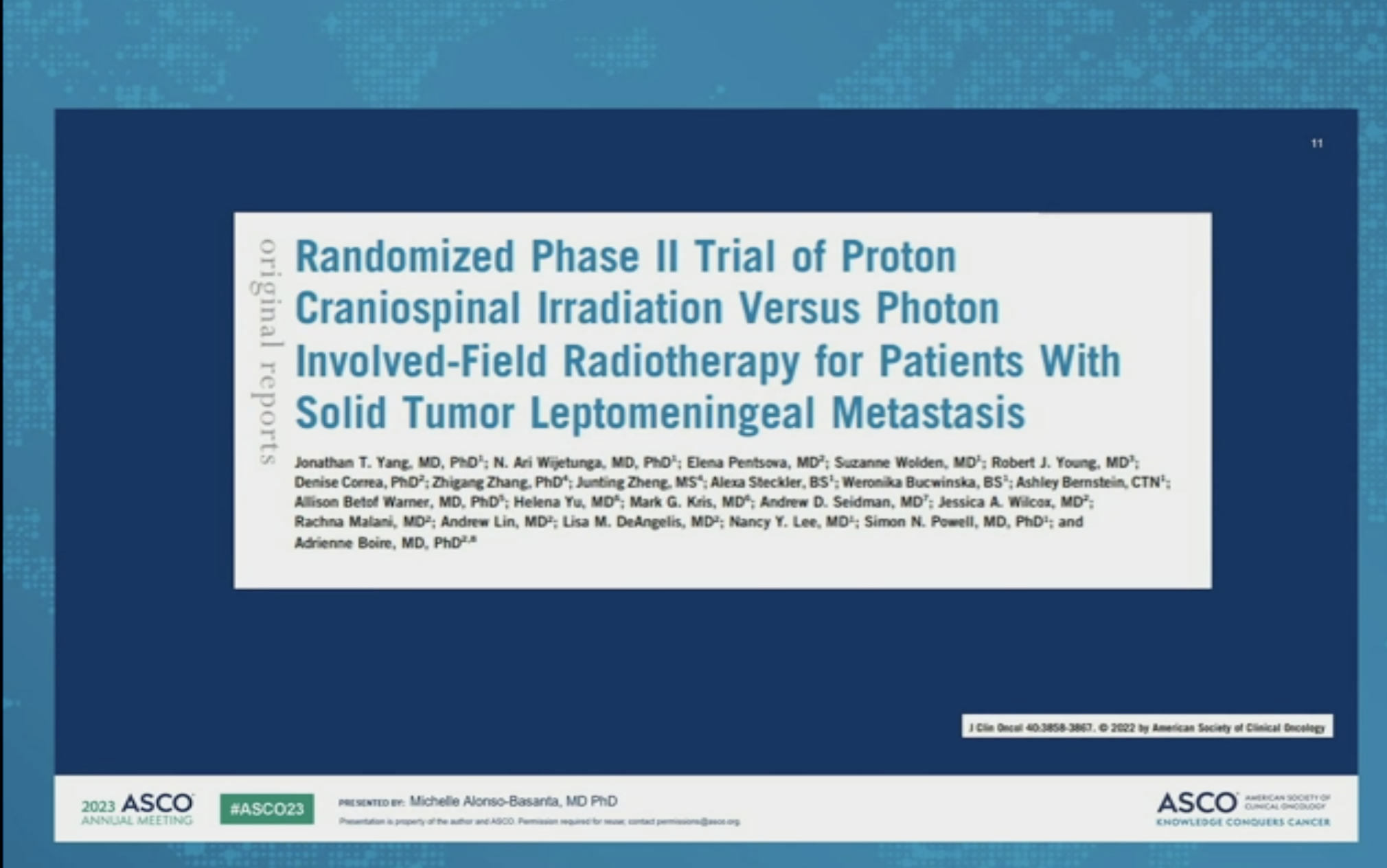

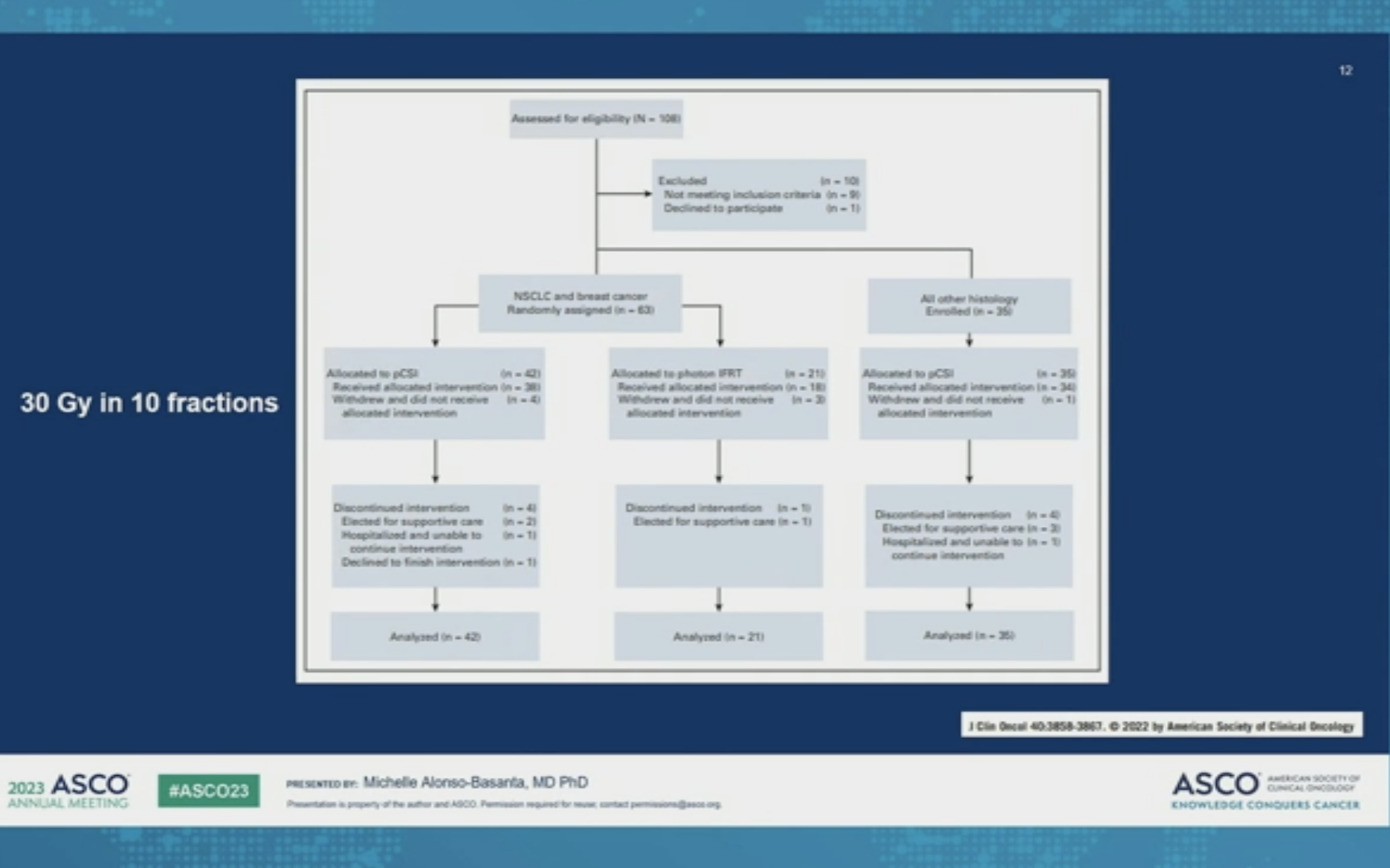

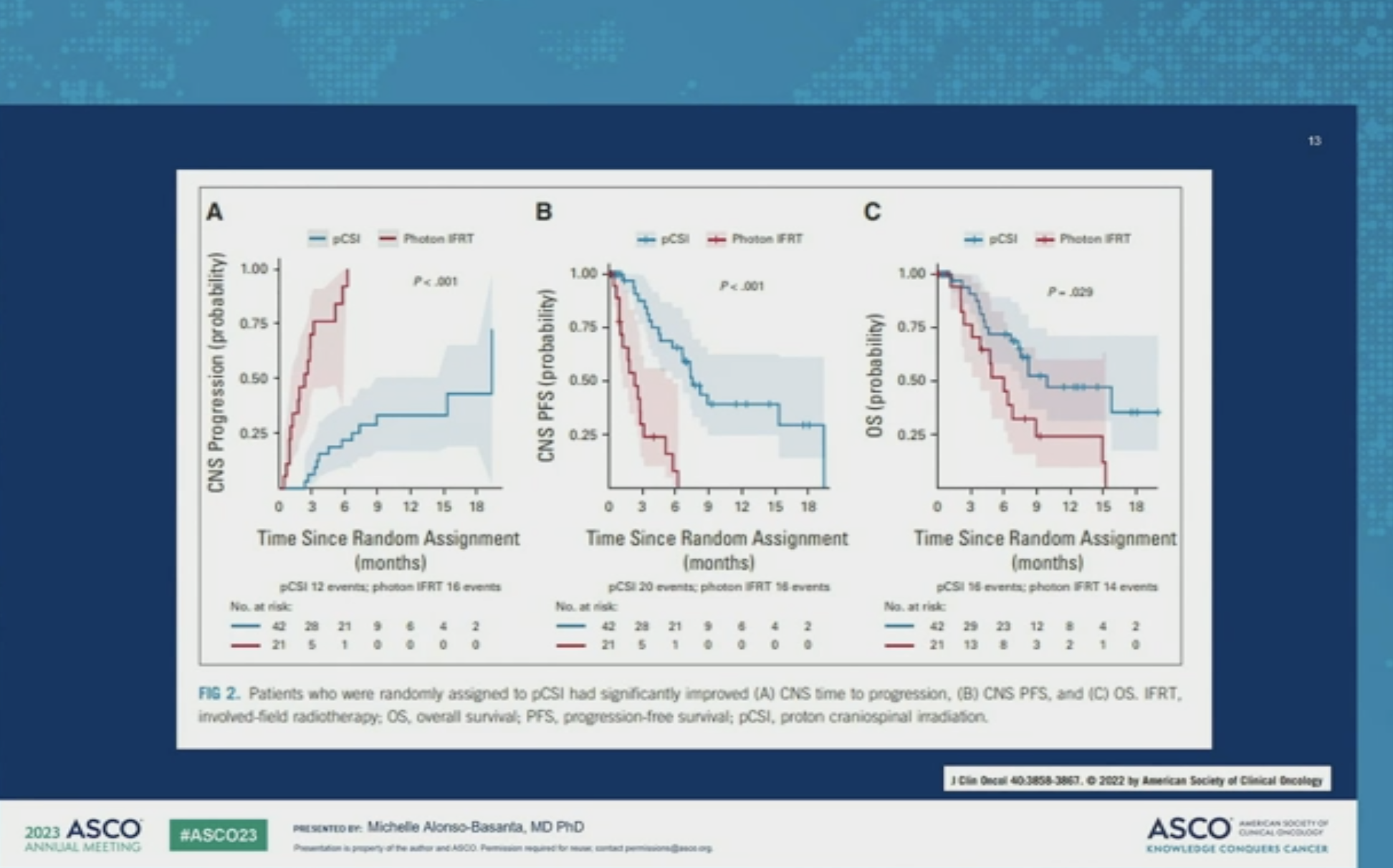

And last year, the Phase II data of pCSI versus involved fields, randomized in patients with primarily non-small cell lung cancer and breast metastases were presented.

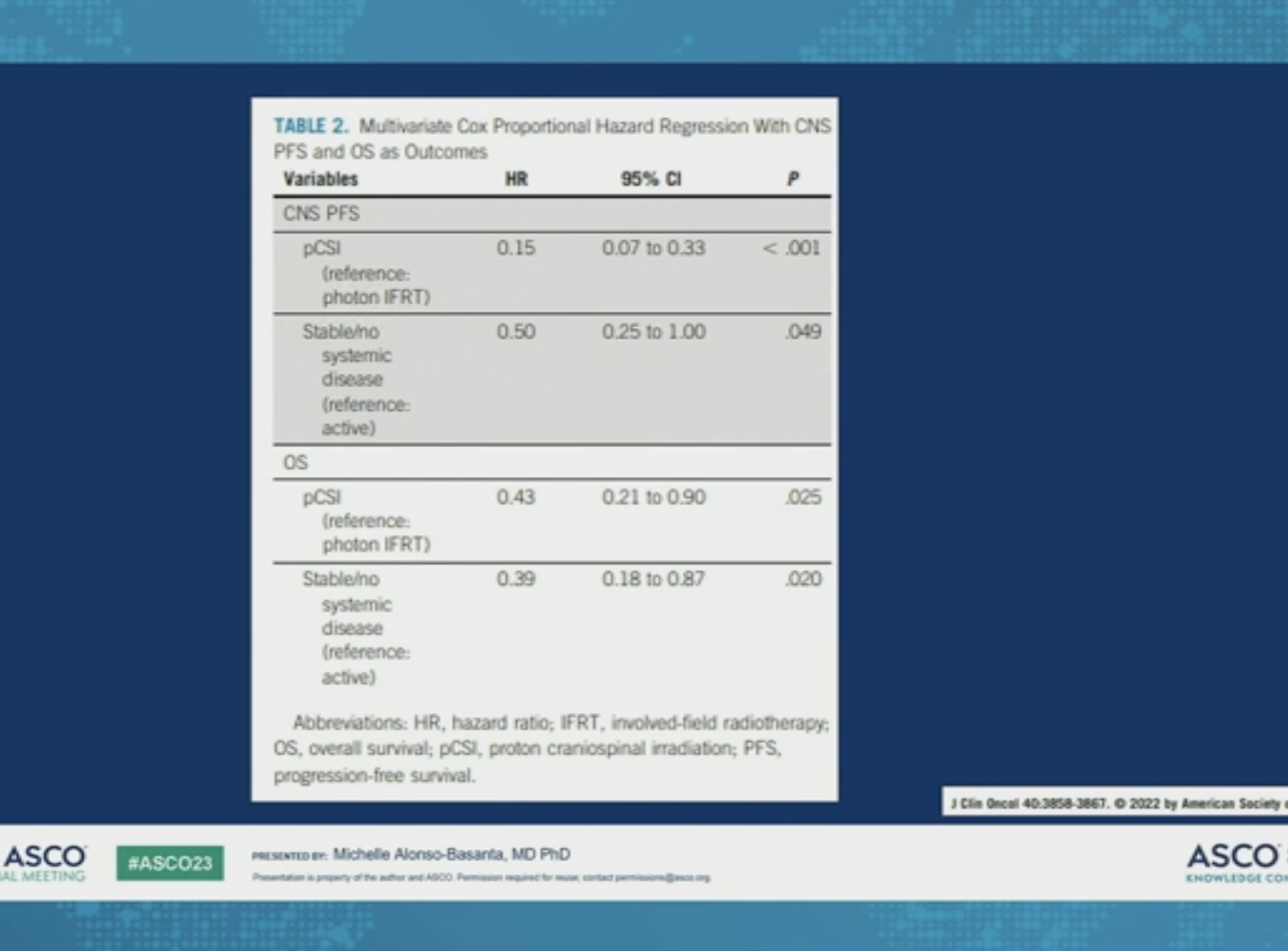

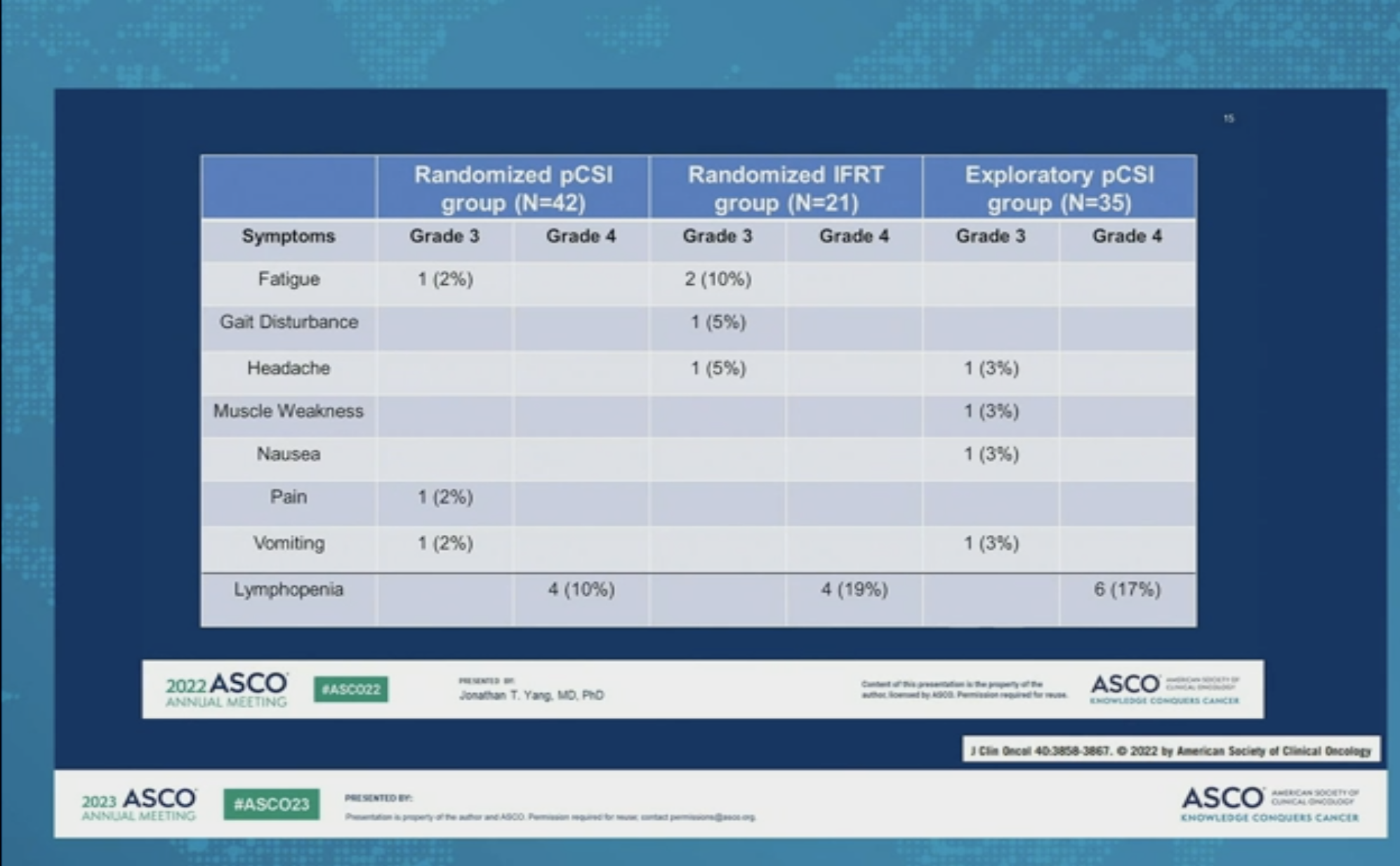

And what they found was encouraging. Good CNS progression-free survival, good overall survival, and in essence, for first time this technique was seriously considered as a viable option for the LMD patients. Toxicity was very favorable.

They saw an improvement in progression-free survival, CNS progression-free survival from 7.5 to 2.3 in overall survival of 9.9 versus six with little differences in grade three, grade four.

Acronyms used in this slide: pCSI is proton craniospinal irradiation, NSCLC non-small-cell lung cancer, TAE adverse effects to treatment.

Great news. But how will it be implemented? Depending on whee you are treated, your radiation oncology center may have forgotten how to do the craniospinal irradiation (CSI). Most teams, trained in that 3-D era who are doing palliative or involved fields, are not necessarily trained in CNS or pediatric radiation.

So you can have lots of varied technologies across the board, but what is essential, is using the right tools at the right time and having an efficient system.

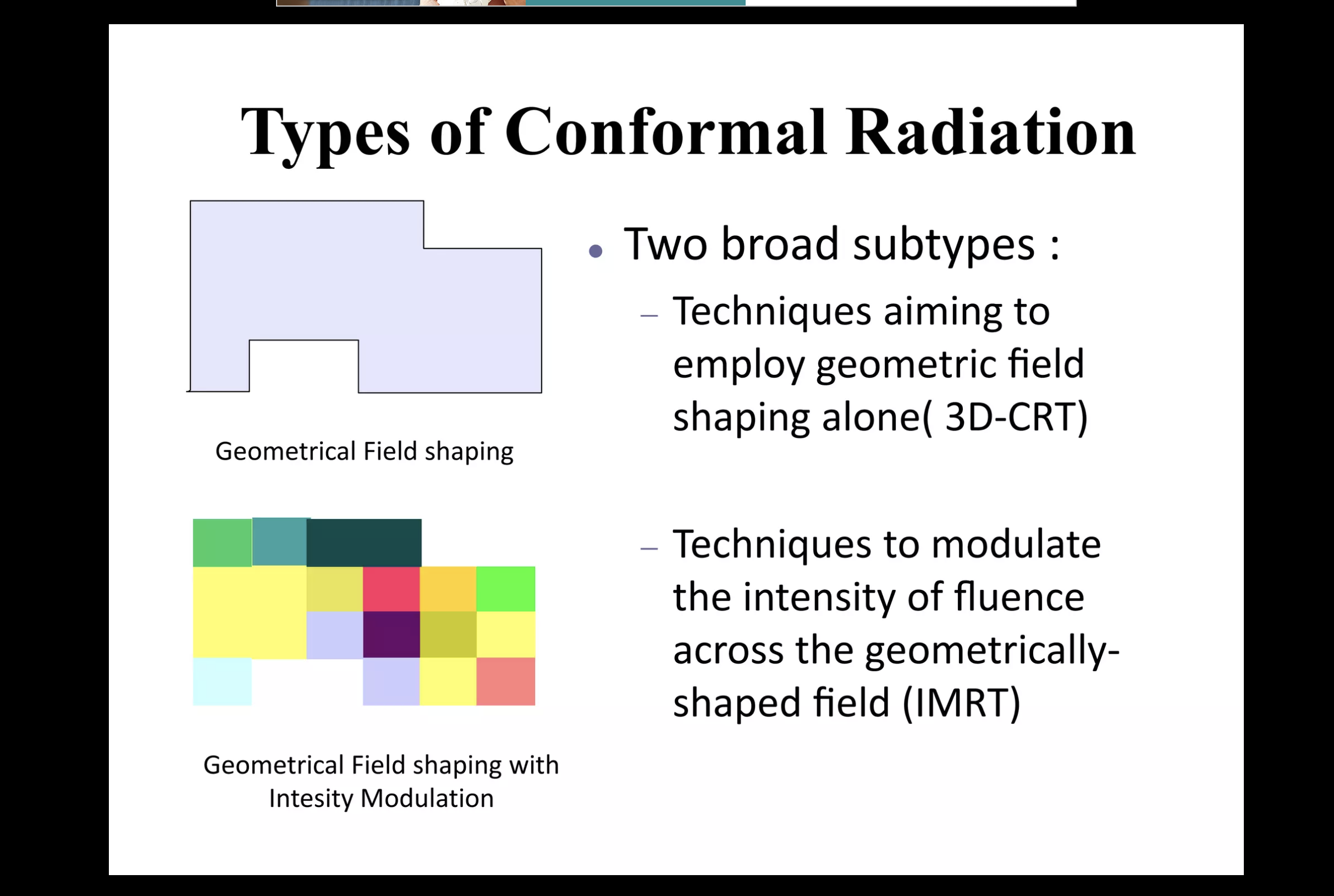

The panels below show the differences in dosimetry and technique for CSI.

The 3-D era gave a lot of dose to a lot of area of the body that really didn't need it.

And so when the field transitioned to an intensity modulated radiation technique or VMAT technique, it did increase the dose to the anterior organs.

TomoTherapy, although very conformal, did spread a lot of dose as well.

pCSI in the last panel looks a lot better.

And really that's why the MSKCC study used pCSI that spares anterior organs at risk.

Given that most patients have had prior radiation, either during their initial primary diagnosis or subsequent palliative radiation of metastases, it's important to try to limit as much as possible the dose to any other structure.

What are the challenges in adults?

Availability. Not everyone feels comfortable treating these patients and not only the physicians, but entire therapy staff.

It is time consuming, both in regards to simulation, in planning, in treating, usually more than 6 hours from simulation to start.

And then there are risks.

Every decision has to be made in conjunction with medical oncologists

It has to be a team decision with the following question to consider:

What is our goal?

How is the patient doing?

What comes next?

It is a tough treatment. When we talk about fatigue, it's not fatigue that you're falling asleep on the couch an hour earlier.It is FATIGUE where you have to set an alarm clock to eat.

The other aspect is the steroid dependence. It has to be considered at all times. It is unacceptable to have a patient on four milligrams every six hours for literally no edema. Steroid dependence in these patients needs to bed decreased quickly.

PT/OT should be considered upfront as well as the dietitians. and social workers involved early on not just for the patients, but the caregivers.

Conclusion

Over the last three years, this podcast has not shied away from difficult subjects. As part of our Road to a Cure series, we have spoken with Dr. Priya Kumtekar, the neuro oncologist for North Western, about this diagnosis and her research.

On our website we have put together every episode that touches upon the subject of LMD.

Follow this link to listen.